I first met Lily and her mother in late winter, about three months after I had arrived in America. In that time, I had established a routine. Every day I took the same path from the boardinghouse where I lived to the restaurant where I worked, and back again. Once a week, on my half day off, I walked toward the water so that the breeze would carry away the oily smell in my hair and the customers’ voices ringing in my ears. I went south to Battery Park, where I watched the ferries loaded with tourists heading for Ellis Island. Or I walked east underneath the Manhattan Bridge, with the traffic rushing overhead, or west to the Hudson River opposite the New Jersey shoreline where boats passed with their white sails aloft.

On my trip over to America, I’d comforted myself with the thought that I would be going to live in a place near the water. I was from Fuzhou, a city on the southeastern coast of China, that was bisected by a river that ran to the ocean. I’d lived in the part of the city that lay on an island so large that you couldn’t tell you were on an island, except that the main sprawl of the city shone across the water. So I told myself that Manhattan was only an island too, no matter how large or inhospitable.

But that winter day, I decided to walk north toward the interior of the city. The frigid weather did little to temper the smells of the Chinatown streets, of garbage and food scraps and rotting fruit. Piles of snow that had fallen weeks before had turned dark and rank, like the ice packed around fish in the markets. Crisp air outlined the buildings and sharpened the honking of car horns and the sound of trucks rumbling down from the bridge. I dug my hands into the pockets of my worn black coat and crossed Canal Street into Little Italy.

Across Broadway, tenements gave way to cast-iron buildings, with stores below and apartments above. These stores were devoted to single, specific things: clothes for children, coats for dogs, bathroom soaps, French tarts. As I headed west, there were fewer stores and more houses, brownstones that rose four or five stories above the narrow, cobble-stoned streets. Some buildings were covered with dead vines and had empty flowerboxes in front of the windows. I tried to imagine what the street would look like in the spring when everything was green and growing. I decided it would look beautiful.

I rounded a corner and came upon a small park shaded by the bare branches of trees. In the other parks I had seen in this city, there were people in suits taking refuge from work, or students with books in their laps, or homeless men sleeping in the sun. In this park, there were only women and children. As I got closer, I saw that these women were not all mothers, or at least not the mothers of the children they were looking after. Their dark eyes rested upon children with skin lighter than their own. Some sat in silence on the benches, while others chatted with each other in sharp-angled languages.

The children who were playing alone fascinated me the most. I watched a little girl with glasses gathering twigs, a boy building a tower out of smooth stones. Another girl appeared to be having a conversation with someone only she could see, an imaginary friend more interesting than any of her real-life playmates. I had always played alone as a child. I didn’t have any brothers or sisters, or children my age living nearby. My grandmother never bothered to supervise me. The trouble I’d get into, she said, I’d get into anyway. Like most children, I played in the narrow winding streets or along the banks of the river.

I closed my eyes, thinking of the small park that I could see from my grandmother’s house. Every morning, our next-door neighbor would go outside with a songbird in a bamboo cage. He would hang the cage on a tree branch and begin his morning exercises. His arms would trace circles in the hazy dawn as dust rose in clouds around his feet. Other elderly people would join him with their birds, and soon the park would be ringed with cages. As a child I imagined that the birds sang from the joy of being outside. Then, when I was older, I thought it was cruel to give the birds just a glimpse of the world from the imprisonment of their cages. Or maybe that one glimpse was enough. I had never been able to decide.

I opened my eyes to see a woman pushing a little girl in a stroller toward my bench. In their own way, they looked as mismatched as any of the other women and children. The woman was American, tall, with red hair shining above an expensive-looking cream-colored coat. The little girl was Chinese, with black hair cut straight across her forehead, and eyebrows so thick that they resembled caterpillars. She appeared to be around two years old and wore a pink coat. When they reached the other end of the bench, the woman gave me a small smile. The little girl looked at me with her thick, dark brows drawn together as if in disapproval. There was something familiar about that look, and I wondered if I’d had the same one on my face when I was a child. Maybe, in some way, the girl recognized that she looked like me.

“Do you want to go play?” the woman asked.

An emphatic nod.

“Go ahead, then. I’ll watch from here.”

The little girl walked toward the other children, taking one uncertain step after the other. The woman opened a book in her lap, but her eyes never left the little girl, as if somehow the sight of the child kept her warm and breathing. That was how I knew, more than anything else, that no matter how different they looked from each other, these two were mother and daughter.

After a while, the little girl turned around and approached her mother. As she got closer, the woman pretended to be absorbed in her book, although a smile remained in the corner of her mouth. It seemed to be a game between them; the little girl tried to get her mother’s attention while her mother pretended to not see her. Finally she grabbed the woman’s hand and tugged on it.

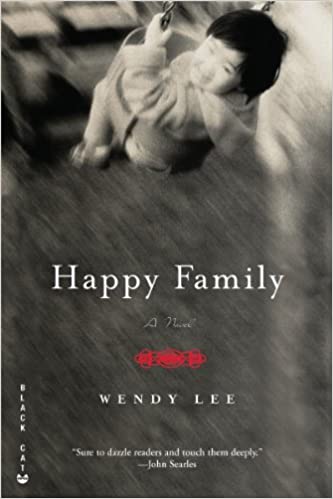

“Shall we go on the swings?” A smile spread across the little girl’s face as if nothing could make her happier. The woman glanced at her watch. “All right, just for a few minutes.”

She placed the book face down and took the little girl’s hand, leaving her bag on the bench. I looked around to see if anyone else had noticed. Surely she didn’t mean to leave her bag where someone could take it. Or maybe she trusted me to look after it. At that thought my hands twitched despite themselves. I wanted to turn the book right side up to see what she was reading, to go through her bag and see what else was inside. I went so far as to turn my head so that I could see what was on the cover of the book. To my surprise, it was a history of Chinese brush painting during the Tang Dynasty.

The woman was pushing the little girl higher on the swing. The arc of her arm and the girl’s flying body made a complete motion, as if a current was passing between them. With her short, paint-brush braids, the little girl reminded me of the child I often saw on a government billboard back home that advertised the desirability of having a girl over a boy, to combat the traditional views. This billboard featured a young couple, the father in a suit and the mother in a blouse and skirt. They held the hands of a little girl wearing a school uniform, her pigtails dancing. Everyone was smiling, their cheeks spots of red. The only thing I had in common with the little girl on the billboard was that I was also an only child. At that age my hair had never allowed to grow past my chin, and my cheeks never got that red unless it was the middle of winter. And, of course, by the time I was old enough to go to school, my parents were dead. They were killed in a factory fire when I was three years old, and my grandmother had brought me up.

Now I noticed that different children were on the swings. I looked around to see that the woman and the little girl had returned to the bench. I moved closer to my end so the woman wouldn’t think I had been looking through her things. She moved past me without a glance and started packing up her bag. Once the little girl had been settled in her stroller, the two moved back the way they had come.

Then I spotted something lying underneath the bench. It was tiny and pink, like a flower or a person’s ear. When I picked it up and brushed it off, I discovered that it was a child’s mitten. I remembered its mate on the little girl’s hand; it was the exact shade of pink as her coat. For a second I thought about putting the mitten in my pocket. The little girl’s mother wouldn’t notice it was missing until they got home, and the girl probably had a drawerful of mittens to choose from. I wanted something to remember the little girl and her mother by, in case I never saw them again. Then it occurred to me that they would never remember me unless I did something to make them remember.

“Excuse me,” I called. The little girl and her mother didn’t turn around. I bit my lip and ran after them. “Excuse me!”

I held the mitten out in response to the woman’s questioning look, my tongue suddenly clumsy.

“This—is yours?”

“Yes,” the woman said, the creases around her eyes deepening as she took the mitten from me. At this proximity I could see that she was older than I had originally thought, perhaps in her early forties. “Thank you.” She turned to the little girl. “Say thank you, Lily.”

The girl stared at me from beneath those ridiculously thick brows.

“Say thank you to the nice lady,” her mother prompted.

“Thank you,” Lily whispered, and then hid her face as if too shy to look at me again.

I watched them until the cream-colored blur of the woman’s coat disappeared at the end of the street. Shivering a little, I realized it was time for me to go too. It was getting late. The sun had dipped behind the brownstones, and the shadows of the children on the swings were lengthening with each flash across the asphalt. I had the walk to Chinatown ahead of me.

A few blocks away from the park, I looked up to see what the names of the streets were so that I could return if I wanted to. I recited them over and over in my head: Greenwich and Jane.