Skip to content

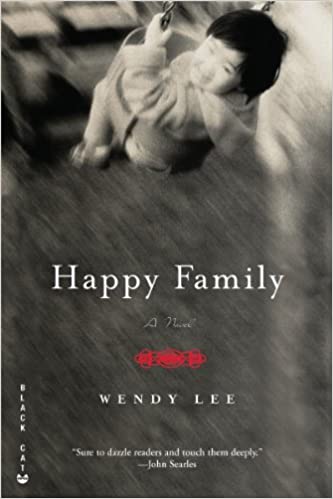

- In the preface, Hua writes to Lily: “I hope that by now your parents have forgiven me for loving you as much as they did. If they are still married, maybe they would even thank me” (p. 5). Is this a letter you think Hua actually sent? If so, how likely is it that Lily’s parents would have forgiven Hua? Or thanked her?

- When Hua learns that her grandparents had once owned a large Western-style house, she wonders why she had never been told. Her grandmother shrugs and says, “What use would that be? What’s lost is lost” (p. 29). Is it understandable that Hua can feel homesick for this house she has never even entered? How is “What’s lost is lost” applicable to other moments in the novel? At one point Hua herself tells Jane that it was fate that led to Lily’s adoption. Do you see this resignation to fate as a particularly Asian attitude?

- “The Chengs are known for bending in the breeze, for giving in to others. That’s how they get what they want. And that’s what you have to do when you get to America. You have to be what other people want you to be, before you can be yourself” (p. 33). Does her grandmother’s advice to Hua seem well-founded for an immigrant? At what cost? Do you think Hua is guided by it? When?

- Is Jane foolishly trusting, even from early on, leaving Lily with Hua at the playground while she runs an errand (p. 58)? When does Hua herself take leaps of faith? How is she rewarded? Are there times you think she is naïve, insouciant or careless? Have you made decisions, leaps of faith, that went against caution and conventional wisdom?

- Talk about some of the complicated issues involved in foreign adoptions. Why is it that Jane went to the trouble and expense of adopting a Chinese baby instead of an American? Hua says about Lily: “There must be some kind of shame attached to her that no one would ever know, least of all her new parents. She had no background, no history, except for what was in her new home” (p. 55). What are the cultural and legal questions she refers to? Hua says later, “She’ll grow up knowing nothing about her homeland. She’ll be worse than those American-born Chinese” (p. 107). Do you agree?

- In the Chinatowns of New York and other cities, transplants can nourish their memories and reinforce their Chinese identity. Elsewhere, immigrants may be forced to assimilate. Which atmosphere do you think serves them better in the end?

- What is the basis for this comment of Hua’s about Lily: “She, for one, would be carrying a lot of weight on her shoulders when she grew up” (p. 164)? How is it related to Hua’s question, “Were all children, in some way, a form of redemption for their parents” (p. 164)? Do you agree with this statement? Why or why not?

- In Lee’s novel how does the geography of New York City become part of the story? What does Hua seek in her perambulations? What about the city reminds her of her childhood in China?

- How does Hua’s playacting lead to a kind of identity theft? (Think of her in Jane’s bedroom and at the playground. In fact, think of her subterfuge at the airport.) Is this a process that happens in stages? In forging a new identity, how is she writing her own story?

- Talk about the title, Happy Family. Do you gather that Richard and Jane have ever been truly “happy”? What are the other marriages like in the book? Her uncle and aunt’s? Her own parents’? Does the California setting offer new hope? How?

- What do you learn from this book about what it is to be Chinese American? Do you see inevitable differences between Asian immigrants and, say, European ones? What do you think happens to Hua after the end of the book? Do you think she will succeed in her new life?